T

here

are

many

aspects

about

property

that

still

elude

researchers,

but

probably

none

more

so

than

depreciation.

Yet,

it

is

such

a

fundamental

factor

determining

the

long-term

returns

from

the

asset

class.

The

first

comprehensive

study

to

attempt

to

quantify

depreciation,

‘Depreciation

in

Commercial

Property

Markets’

was,

using

UK

IPD

data

and

CBRE

data,

undertaken

in

July

2005

(1)

.

Seven

recognised

previous

studies

had

estimated

the

depreciation

rate

for

office

rental

values,

producing

results

ranging

between

0.8%

p.a.

and

3.0%

p.a.

Some

studies

had

also

looked

at

yield

or

capital

value

depreciation,

although

there

was

evidently

difficulties

in

differentiating

between

the

effect

of

depreciation

and

the

other factors that influence yield shifts.

An

initial

analysis

of

the

IPD

UK

database

by

the

July

2005

study

revealed

that,

over

the

period

1981

to

2003,

the

average

age

of

the

properties

had

fallen

slightly,

from

26.8

years

to

26.1

years.

That

fall

masked

two

things.

First,

in

terms

of

the

IPD

Index

time

series,

in

most

years

the

average

age

rose

by

more

than

the

12

months

that

had

elapsed,

suggesting

that

investors

(who

were

mainly

institutions)

were

selling

more

modern

property

and/or

buying

older

property.

The

exceptions

were

seen

during

cyclical

bouts

of

development,

of

which

the

most

striking

period

was

between

2000

and

2003,

when

the

average age fell by one year at the All Property level.

Second,

there

were

significant

differences

between

the

sectors.

Standard

retail

units’

average

age

rose

by

13.9

years,

industrials

by

6.9

years,

while

offices

fell

by

0.3

years.

Within

the

office

sector,

West

End

of

London

had

become

older,

while

the

City

of

London

and

South

East

of

England

had

become

younger.

The

oldest

properties

were

in

standard

retail

units

which,

by

the

end

of

2003,

had

an

average

age

of

62.5 years.

The

fact

that

standard

retail

units

had

outperformed

offices

over

the

period

and,

yet,

had

the

greatest

ageing,

raises

an

important

question.

What

are

we

trying

to

measure

in

depreciation?

The

report

fixes

that

firmly

as

meaning

the

loss

in

value

due

to

age,

although

there

is

an

acknowledgement

that

some

locational depreciation may have been included in the numbers.

But

if

depreciation

equates

to

age,

then

it

suggests

that

the

investor

universe,

as

measured

by

IPD,

was

either

oblivious

to

it

(by

allowing

the

portfolio

to

depreciate

and

not

countering

it),

or

it

believed

that

it

was

a

factor

less

significant

than

the

other

ones

that

determine

performance

(such

as

sector,

or

building

quality).

There

is

also,

however,

the

locational

issue,

to

which

the

report

made

passing

reference.

Clearly

when

we

are

considering

ageing,

we

are

merely

referring

to

the

building:

the

land

on

which

it

sits does not age.

Indeed,

for

as

long

as

populations

grow

and

their

demands

increase,

the

finite

resource

of

land

should

see

increasing

competition

for

it.

Where

that

demand

is

strongest

–

in

recent

times

in

city

centres

–

we

should

expect

appreciation

to

be

strongest.

And

where

the

economic

utility

of

the

land

is

highest

–

for

instance

housing

highly-paid

office

professionals

–

the

land

value

should

be

highest.

These

locations

will,

to

some

extent,

change

over

time,

and

that

presents

a

particular

problem

in

trying

to

estimate

depreciation rates for the combined value of land and buildings.

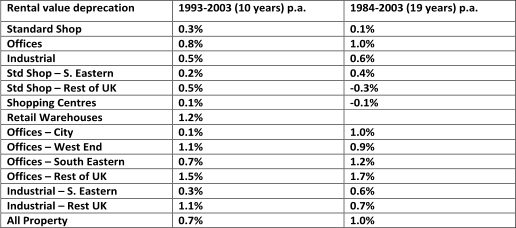

Nevertheless, the report results are shown in the table below

The

lower

depreciation

rate

in

the

more

recent

period

implies

that

the

rate

of

inflation

has

slowed,

but

the

report

was

not

able

to

offer

a

reason

for

that.

It

should

also

be

noted

that

there

are

a

couple

of

negative

figures

in

the

table

–

although

not

very

large

–

but

the

report

could

not

fully

account

for

those.

Nevertheless,

the

1%

All

Property

figure,

taken

from

the

full

period

of

data,

has

become

something

of

‘a

rule

of

thumb’

amongst

researchers

and

although

it

is

derived

from

UK

data,

has

received a universal application in developed European markets.

There

was,

however,

some

concern

in

the

research

community

that

the

sample

used

for

the

analysis

understated

the

rate

of

depreciation

because

it

was

more

prime

than

the

universe

of

all

properties.

Of

course,

that

pre-supposes

that

prime

property

depreciates

at

a

faster

rate

than

older

secondary

property.

Europe next and then back to the UK

An IPF report (2) published in March 2010 on depreciation in Europe used a similar methodology (3) to the UK analysis, but produced quite a strange set of results. Rental depreciation rates, over a 10-year period to 2007, ranged from 5% p.a. in Frankfurt to an appreciation rate of 2% p.a. in Stockholm. At the time, this report sparked much discussion seeking an explanation for the results, which included questioning the quality of the rental value data, although there was no wholly satisfactory conclusion. There were also many inconsistencies in terms of the age profile of depreciation, which appeared to vary between cities. It was suggested that depreciation seems to increase in stronger lettings markets so that the existing stock seem to lose out to newer properties at such times. However, when markets are weaker, existing properties do relatively better than new by not depreciating as much. I think that that was a particularly interesting observation, which I interpret as meaning that new developments (or refurbishments) are a causal effect of depreciation – to the existing stock. While there would still be physical depreciation to the existing stock without new developments, that can be largely fixed by maintenance expenditure. But if there is no better product, the effects of economic or functional depreciation would be much reduced, maybe to zero, and those are the more important forms of depreciation – rather than physical depreciation – in our evolving markets. A later report on the UK (4) used a different approach (5) , but this was applied to only offices and industrial property conceding, to some extent, the difficulties of applying it to retail property. An early question addressed by the report was the shape of depreciation over time. Is it linear, geometric (fast at the beginning), s-curve (slow, fast, then slow), or even a one-off event? While acknowledging that previous studies had produced no consensus, the report concluded that high quality properties, as measured by their rental values, suffered from higher rates of depreciation, and that depreciation rates seem to slow for very old properties. Nevertheless, the findings for age- related variations were disappointing, suggesting that it is quite difficult to identify the relationship, assuming that it exists. When academic studies fail to get to a set of fully satisfactory conclusions, there is always a temptation to rationalise the causes, such as the quality of the raw data. Of course, if the causes could be properly identified, then it is likely that they could be addressed in some way. My belief is obsolescence is too complex to model properly with the limited data that we have available. One only has to consider, as a starting point, the three different forms of obsolescence: 1 . Physical, defined as the loss in value due to ageing and wearing out of the building and its services 2 . Functional, which is the inability of a building to provide the economic utility required by the occupier in terms of the use for which it was built. This may be because the requirements or processes of the business have changed, often because of technological advances (such as the introduction of air conditioning or computers), although sometimes because standards (say regulatory) change 3 . Economic, also called locational obsolescence, the loss in utility due to factors external to the property itself. For example, the opening of a new shopping centre may move the ‘prime retail pitch’ to a different locationToo difficult

Add to this mix the two components of a property – the physical building and the land – which may experience depreciation (or, in the case of the land, appreciation) at different rates. Then there is the cycle which causes depreciation to cluster in the down-phases of markets. Each economic and property cycle has its unique characteristics in terms of drivers, which have different effects on depreciation rates. Put all of these factors together with buildings and tenants that each form a unique combination, and it is, I think possible to understand the difficulties of using statistical techniques to achieve a simple answer as to what is the rate of depreciation. But if it is too complex even for a mathematical analysis, does that mean that we cannot get a grip on this subject? I do not believe so, and my approach is simply this. All buildings were built for a purpose. The ones in the best locations at the time would have been built as prime. Consider one of those; an office building in the City of London built 20 years ago, for example. What is its rental value now? You might estimate that to be GBP50/sq ft/year. Now imagine that you were building on a prime location today, to a quality specification and modern requirements. What is the grade-A rent per square foot? Say GBP75/sq ft/year. The yields may now be 5.5% for the older building and 4.5% for the new one. A rough and ready calculation places capital values of, respectively, GBP900 and GBP1,650. The difference represents a measure of the depreciation of the building over the period. The answer is 2.0% p.a. for the rental value, and 3% p.a. for the capital value. Obviously, the answer will vary between sectors, locations and building types, but the approach does have the benefit of including all forms of depreciation. For Paris CBD, where the standard form of quality office building is a ‘Haussmannian’ five-story, plus basement and attic rooms, building constructed somewhere between 1853 and 1920, the rate of depreciation is very low – simply because there is little development to replace them. In effect, the planning restrictions have depressed depreciation within central Paris, and there is little difference in value between a building of 1850 and of 1920. While there is the ’other Paris CBD’ of La Défense, which offers relatively modern large floor plates, the differences between the two are so great, that the substitutability is very limited. Paris CBD depreciation is therefore more physical than economical. These are rough approaches to the issue but, I would argue, it is better to be roughly right than precisely wrong. Of course, you will then need to think about whether depreciation will be faster in the future – as I would argue – than it has been in the past. That is where understanding the drivers helps. Footnotes (1) ‘Depreciation in Commercial Property Markets’, V. Law, N. Crosby, S. Devaney, and A. Baum, sponsored by IPF, July 2005. What is known as cross-sectional regressions (2) Depreciation of office investment property in Europe, Neil Crosby, School of Real Estate and Planning, University of Reading, S Devaney, M Frodsham, R Graham, and C Murray, March 2010, funded by the IPF Research Programme published in March 2010 on depreciation in Europe used a similar methodology (3) This was what is known as a longitudinal study, but the basic methodology was fairly simple. The IPD data represented the performance of real property, including depreciation. The CBRE data – like much other agents’ data – represented hypothetical prime property, which is assumed to be prime at every data point and, therefore, ignored depreciation. Subtracting one from the other should, theoretically, produce a rate for depreciation. (4) Modelling Causes of Rental Depreciation for UK Office and Industrial Properties, part of the IPF Research Programme, N Crosby, S Devaney, and A Nanda, June 2013 (5) What is known as cross-sectional regressionsMeasuring depreciation

Ltd